EUROPEAN COMMISSION

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Brussels,1.6.2018

SWD(2018) 301 final

COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT

IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Accompanying the document

Proposals for a

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing rules on support for strategic plans to be drawn up by Member States under the Common agricultural policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the financing, management and monitoring of the common agricultural policy and repealing Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013

- Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulations (EU) No 1308/2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products, (EU) No 1151/2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs, (EU) No 251/2014 on the definition, description, presentation, labelling and the protection of geographical indications of aromatised wine products, (EU) No 228/2013 laying down specific measures for agriculture in the outermost regions of the Union and (EU) No 229/2013 laying down specific measures for agriculture in favour of the smaller Aegean islands

{COM(2018) 392 final}

{COM(2018) 393 final}

{COM(2018) 394 final}

{SEC(2018) 305 final}

Annexes

Table of contents

Annex 5: Results of quantitative and Multi Criteria Analysis

1.

Introduction

2.

Results of quantitative analysis

2.1.

Support viable farm income and resilience across the EU territory

2.2.

Increasing the environmental and climatic benefits of the CAP

3.

Multi Criteria Analysis

3.1.

Introduction

3.2.

Effectiveness of policy options

3.3.

Efficiency of the policy options: simplification

3.4.

Promoting knowledge and innovation in agriculture and rural areas: Modernisation

3.5.

Policy coherence

3.6.

Cross cutting: Improving sustainable development for farming, food and rural areas

Annex 5.1 Policy options for the IA

1.

Elements common to all options

1.1.

Budgetary framework

1.2.

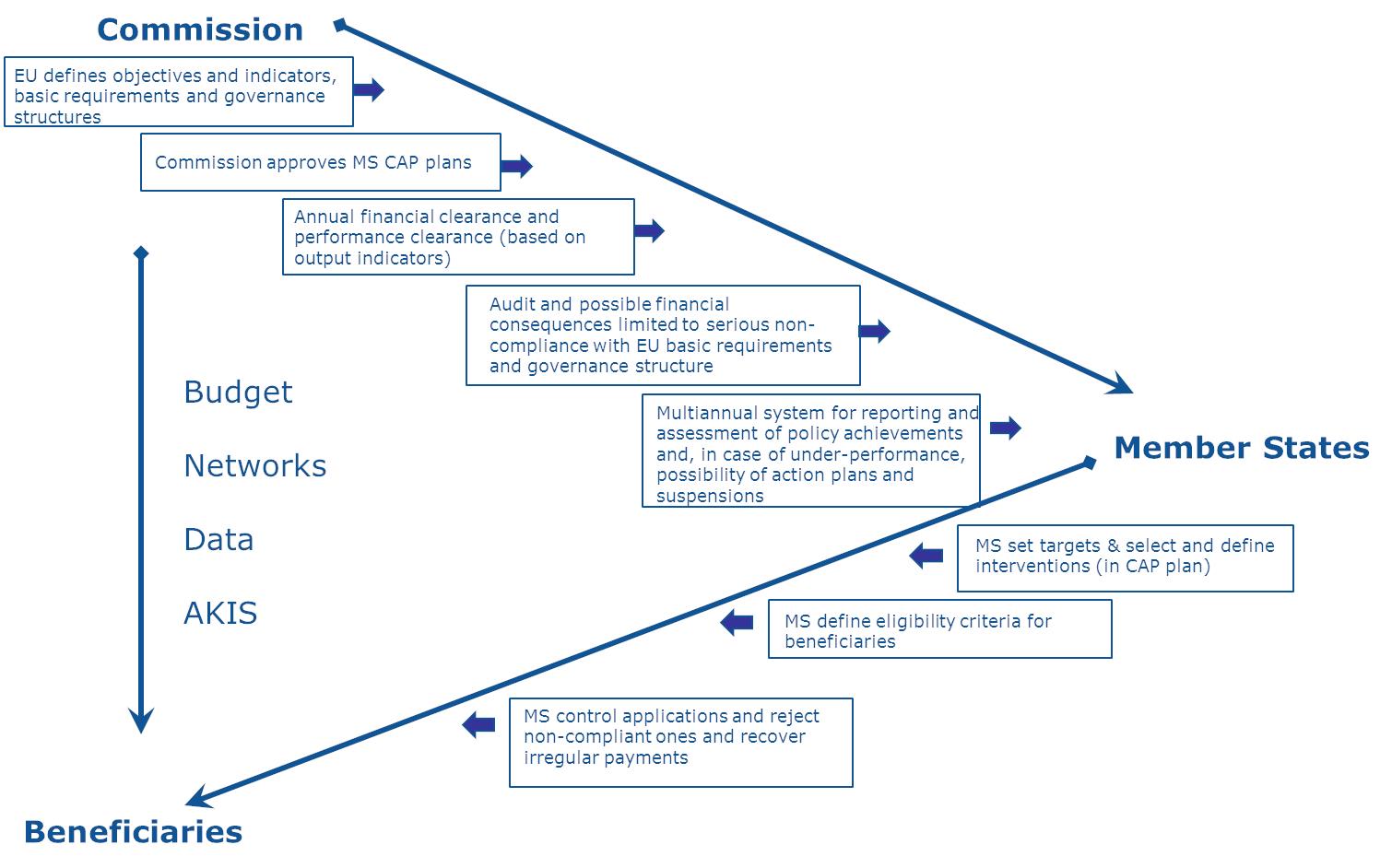

Delivery model and planning

1.3.

Knowledge, innovation and technology

1.4.

Market-related measures

1.5.

Conditionality and green architecture of the CAP

2.

Options description

2.1.

Option 1: Updated baseline

2.2.

Option 3: Incentives for environment, climate action and health

2.3.

Option 4: Jointly address environmental and economic sustainability

2.4.

Option 5: Focus on small farms and the environment

Annex 5.2 Methods and tools

1.

Introduction

2.

Brief description of the main models and tools used in the IA

2.1.

MAGNET

2.2.

Aglink-Cosimo

2.3.

CAPRI

2.4.

IFM-CAP

88

2.5.

AIDSK

2.6.

RUSLE 2015

2.7.

Century model

2.8.

Standard Cost Model

2.9.

Workshops with experts

2.10.

Intervention logic based on expert judgement

2.11.

Multi-criteria-analysis

3.

Description of tools used in the different phases

3.1.

Evaluation of baseline

3.2.

Assessing the impact of options

3.3.

Addressing uncertainties

3.4.

Comparing the baseline and the options

Annex 5.3: Objectives used in the MCA

Annex 5.4 – Non-productive elements in the EU

Annex 5.5: Capping

Annex 5.6: Share of direct payments received by biggest beneficiaries and biggest farms

Annex 5.7 – Income variability

Annex 6: Promoting Modernisation

1.

Enhancing Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS) and strengthening links with research

2.

Strengthening of farm advisory services within the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems

3.

Enhancing interactive innovation

4.

Supporting digital transition in agriculture

Annex 7: Simplifying the CAP

120

1.

Administrative burden under the CAP

121

2.

CAP simplification and modernisation: changes considered for post-2020

125

2.1.

The new delivery model

125

2.2.

Changes under the Common Market Organisation

126

3.

A CAP oriented towards performance

129

4.

Scope for reducing administrative burden

129

4.1.

Simplification under the new delivery model

129

4.2.

Strategic design and delivery for administrative burden reduction

132

4.3.

Assessing administrative burden reduction

135

5.

Towards efficient CAP design and delivery

140

Annex 8 - Behavioural evidence from focus groups with European farmers on approaches to encourage more environmental-friendly practices

141

Annex 9 – Bibliography

148

Annex 10 – Glossary

163

Annex 5: Results of quantitative and Multi Criteria Analysis

Acknowledgments

DG AGRI would like to thank colleagues in JRC for the support and close collaboration on the modelling of the impacts (JRC Seville) and the environmental aspects (JRC Ispra). Also for the qualitative assessment on environmental aspects, JRC Ispra was involved.

Glossary

|

Term or acronym

|

Meaning or definition

|

|

AECH

|

Agro Environment, Climate and Health measures

|

|

AKIS

|

Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems

|

|

AMR

|

Antimicrobial Resistance

|

|

ANC

|

Areas facing Natural Constraints

|

|

AWU

|

Annual Work Unit

|

|

BAS

|

Baseline

|

|

BP

|

Basic Payment

|

|

BPS

|

Basic Payment Scheme

|

|

CAP

|

Common Agricultural Policy

|

|

CATS

|

Clearance Audit Trail System

|

|

CO2

|

Carbon dioxide

|

|

COP

|

Cereal, Oilseed and Protein crops

|

|

DG

|

Directorate-General

|

|

DP

|

Direct Payments

|

|

EBA

|

Everything but arms

|

|

ECO

|

Economic Challenges Working Group

|

|

EEA

|

European Environment Agency

|

|

EIP

|

European Innovation Partnership

|

|

ELS

|

Entry-Level Scheme

|

|

ENV

|

Environmental and Climate Challenges Working Group

|

|

ES

|

Economic Size

|

|

FADN

|

Farm Accountancy Data Network

|

|

FAS

|

Farm Advisory System

|

|

FNVA

|

Farm net value added

|

|

GAEC

|

Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions

|

|

GGE

|

Greenhouse Gas Emission

|

|

GHG

|

Greenhouse Gas

|

|

GI

|

Geographical Indication

|

|

GNB

|

Gross-Nitrogen Balance

|

|

H2020

|

Horizon 2020

|

|

ha

|

hectare

|

|

IA

|

Impact Assessment

|

|

IPM

|

Integrated Pest Management

|

|

IST

|

Income Stabilisation Tool

|

|

JRC

|

Joint Research Centre

|

|

kg

|

kilogramme

|

|

km

|

kilometre

|

|

LDC

|

Least Developed Countries

|

|

LFA

|

Less Favoured Areas

|

|

MCA

|

Multi Criteria Analysis

|

|

MO

|

Main (Policy) Objective

|

|

MS

|

Member States

|

|

N

|

Nitrogen

|

|

NMP

|

Nutrient Management Plans/Tools

|

|

NUTS

|

Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics

|

|

Mt

|

Million tonnes

|

|

OO

|

Operational Objective

|

|

PCD

|

Policy Coherence for Development

|

|

PO

|

Producer Organisation

|

|

pp

|

percentage point

|

|

RD

|

Rural Development

|

|

RM

|

Risk Management

|

|

SAPS

|

Single Area Payment Scheme

|

|

SDG

|

Sustainable Development Goals

|

|

SME

|

Small and medium-sized enterprise

|

|

SO

|

Specific Objective

|

|

SOC

|

Socio-economic Challenges Working Group

|

|

SPS

|

Single Payment Scheme

|

|

T

|

Tonne

|

|

TAMS

|

Total Aggregate Measurement of Support

|

|

UAA

|

Utilised agricultural area

|

|

VA

|

Value Added

|

|

VCS

|

Voluntary Coupled Support

|

|

YF

|

Young Farmer

|

|

Yr

|

Year

|

1.Introduction

This annex first summarizes the quantitative results of the option comparison. The second part merges these results with qualitative results from a group expert judgement in a Multi Criteria Analysis (MCA). In annex a detailed description of the options (annex 5.1), the analytical tools and methods used (annex 5.2) and the objectives (annex 5.3) can be found. Annex 5.2 also details how the MCA was organized and which experts participated in the process. The qualitative assessment was organized to complement the modelling exercise as the applied models are not capable of capturing all effects of the tested instruments. Especially on the social (and to a lesser extend the environmental) dimension of the policy, expert judgement offers an important contribution to the analysis. The qualitative assessment also allows unveiling the reasons behind differences in option scores.

On some occasions the modelling and expert judgement diverge, which can be linked on the one hand to the fact that the models cannot capture all intended policy effects and on the other hand the under- (or over-) estimation of some effects by the experts. For these reasons it is fruitful to combine both approaches. Where appropriate, these differences are highlighted and discussed.

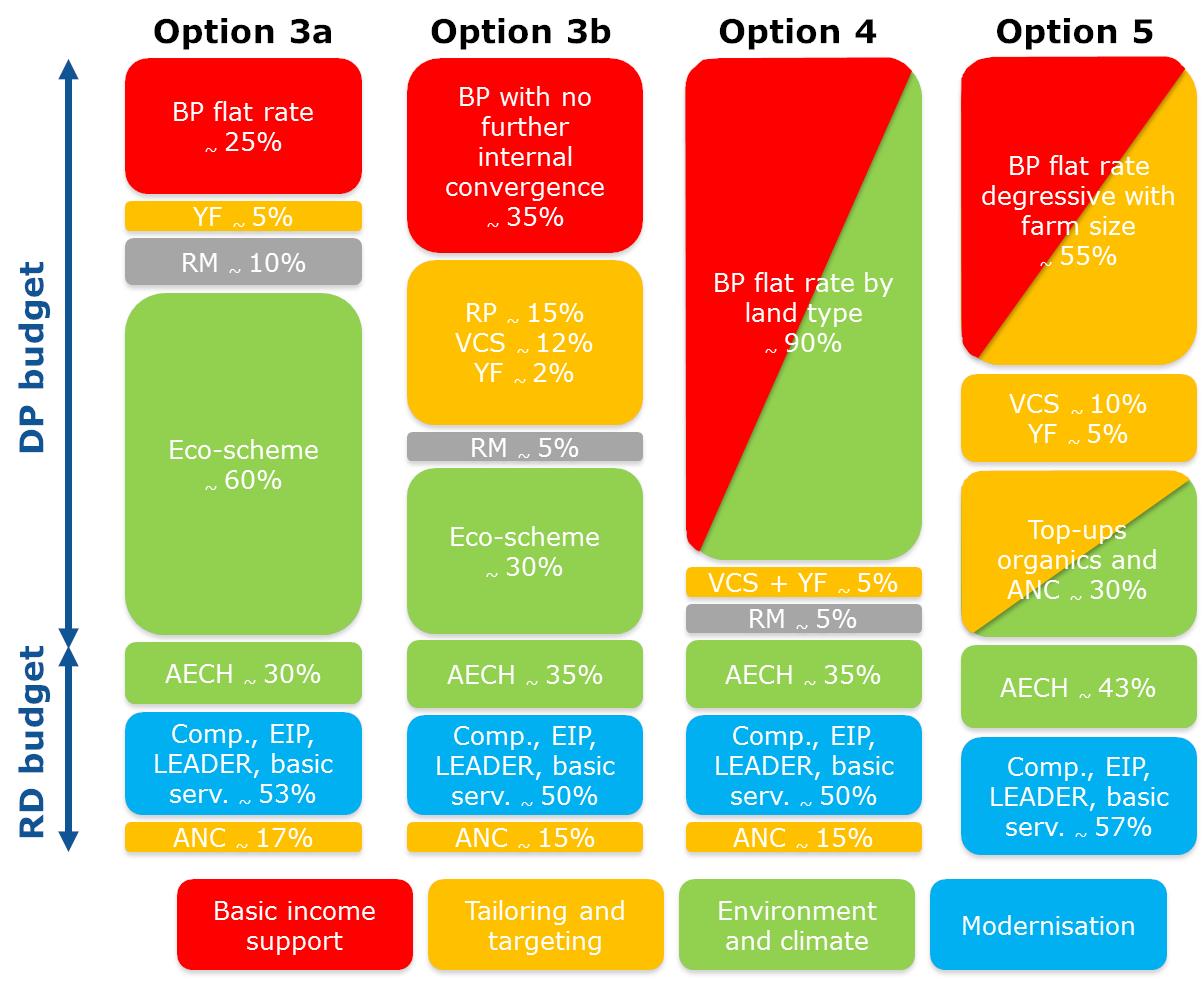

The following two tables highlight the assumptions for key CAP interventions.

Note: Baseline with the post-Brexit budget cut is referred to as Option 1 in Annex 5.

Table 1.1 Income support and redistribution in the options

|

|

Option 1

|

Option 3a

|

Option3b

|

Option 4***

|

Option 5

|

|

Decoupled payments*

|

High

|

Very small

MS flat rate

|

Medium

|

Strong

flat rate by land type

|

Medium

degressive with size

|

|

Voluntary coupled support

|

High

|

0

|

High

targeted to EU goals and improving competitiveness

|

Small

targeted to extensive livestock

|

Potentially high targeted to EU goals

|

|

Areas with natural constraints

|

Lower further to Brexit

|

Maintained

in pillar II

|

Maintained in pillar II (higher national funds)

|

Maintained in pillar II (higher national funds)

|

Increased

top up in pillar I

|

|

Payment redistribution

|

Top up to first ha in 8 MS.

Degressivity in 14 MS from 150 000 EUR, % cut vary by MS from 5 to 50%**

|

0

|

To small-medium farms via a top up to first 30 ha

|

To farmers with lower income

via an increase in support to permanent grassland

|

To small-medium farms

via the modulation of support by size

|

|

Capping per farm (with salaries correction)

|

Limited,

in 8 MS

threshold from 150 000 to 500 000 EUR

|

100 000 EUR

|

100 000 EUR

|

100 000 EUR

|

60 000 EUR

|

|

Capping per ha

|

|

|

1 000 EUR

|

|

|

|

Minimum requirements

|

Threshold in EUR or ha varies from 0.5 to 4 ha and from 100 to 500 EUR

|

2 ha

|

2 ha

|

2% of ag. income (varies by MS, from 100 to 1 000 EUR)

|

Status quo

|

* includes the basic payment scheme, the single area payment scheme and greening

** e.g. amounts above 150 000 EUR per farm (with salaries correction) are cut by 5% in BG and by 50% in IT.

*** options 4a and 4b are similar in terms of direct payments implementation.

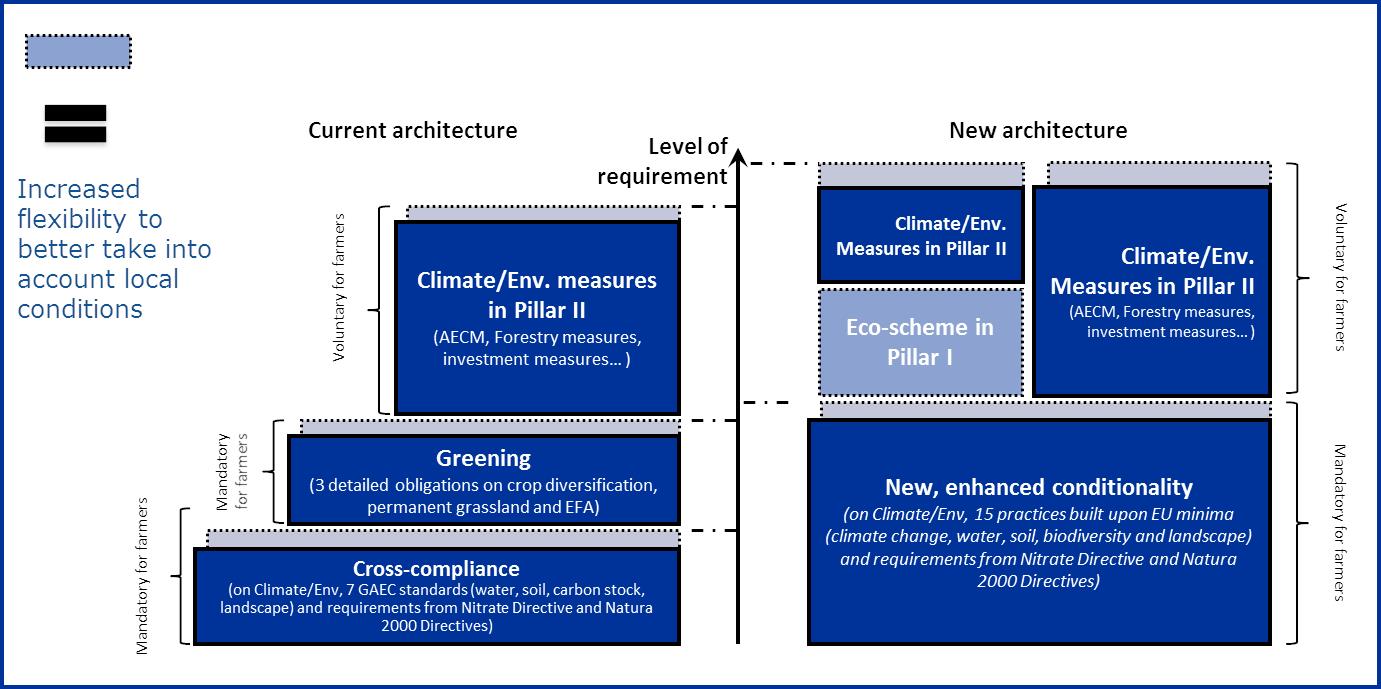

Table 1.2 The green architecture in the options

|

|

Option 1

|

Option 3a

|

Option3b

|

Option 4a

|

Option 4b

|

Option 5

|

|

Conditionality

|

+

|

++

|

++

|

++++

|

++

|

++

|

|

Other interventions

|

|

|

|

Support redistribution to permanent grassland and targeted coupled support to extensive livestock

|

Targeted coupled support to extensive livestock

|

|

Eco-scheme (voluntary)

|

|

++

|

+

|

|

|

|

|

Top ups

|

|

|

|

|

|

++

|

|

AECH

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

+

|

++

|

2.Results of quantitative analysis

The findings are presented according to the corresponding objectives

2.1.Support viable farm income and resilience across the EU territory

2.1.1.Provide income support in a targeted way

Negative impact of policy changes on average EU income level

Farm income is negatively affected in all options compared to baseline and option 1 for three main reasons:

1.The budget cut and redistribution of support (notably to small and medium size farms).

2.The reduction in direct payments because of re-allocation of funds to risk management (options 3 and 4): this leads to a decrease of the EU average income level in 'normal

' years assessed here. In years of strong yield or price drops, risk management tools can help farmers to mitigate negative impacts on income.

3.The changes in farm practises to increase the environmental and climatic performance of the CAP: the land re-allocation to fulfil crop rotation restriction, the costs to comply with the other green requirements and the obligation to dedicate more land to non-productive elements lead to a significant decline in cereal area in favour of set aside and fallow land, and thus a decline in market revenue.

Note of caution: farm income decline is overestimated, as the model used does not account for structural change, price feedback

and longer term benefits due to changes in production systems. Nonetheless, the analysis gives an accurate indication of the relative performance of the various options in the short-term, as well as of the expected impact on different farm types and sectors.

This modelling exercise does not account for structural change, i.e. it assumes the same number and size of farms in all simulations. However, large income decreases such as those expected for certain sectors/options might push less efficient farmers out of business.

The largest income

drop is in option 3a (-10% relative to option 1), where the switch of priority to risk management is the strongest and then in option 4a (-8%), the two options with the highest environmental ambition. The income decline is smaller and of a similar range in option 3b, 4b and 5 (around -5% compared to option 1). A linear cut (option 1) would drive a smaller drop on average (-2%) but without addressing the challenges ahead and certain sectors and MS would be more strongly hit.

In option 3, the uptake of the voluntary eco-scheme is simulated at EU level at 98%, varying from less than 90% in Portugal to 100% in MS with large areas of permanent grassland. It means that in view of the eco-scheme adoption costs and the unit payment level simulated here, only a small number of farmers chose to opt out from the eco-scheme. It shows that the unit payment level, which was set assuming a 100% uptake, is a significant incentive for farmers to adopt the changes in practises, all the more because of the importance of support in farmers’ income. It highlights also the difficulty that MS will face in maximising environmental-climatic-health benefits and budget allocation at the same time on an annual basis. Said differently, it highlights the difficulty to predict in advance the level of uptake and the most appropriate aid level in view of the requirements.

Table 2.1 Impact of policy options on EU average farm income

|

|

Relative to baseline

|

Relative to option 1 (baseline with cuts)

|

|

|

1

|

3a

|

3b

|

4a

|

4b

|

5

|

|

Direct payments

|

-10%

|

-75%

|

-40%

|

-6%

|

-6%

|

-26%

|

|

Total support

|

-10%

|

-11%

|

-7%

|

-4%

|

-4%

|

-6%

|

|

Income

|

-2%

|

-10%

|

-5%

|

-8%

|

-5%

|

-5%

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

The impact of policy options varies strongly by type of farming

Cattle and sheep producers are strongly affected in options where support is significantly cut (option 1 and 3) and where coupled support is removed (option 3a). In option 1, the income of cattle producers is reduced by around 10%, an additional 25% cut compared to option 1 occurs in option 3a (Graph 2.2), where the number of cattle heads declines by 3% relative to option 1. The drop in income of sheep producers reaches 4% on average in option 1 and an additional 6% drop is implied in option 3a.

The drop in income is attenuated when these sectors benefit from re-allocation of support for their contribution to environmental sustainability via coupled support (options 3b, 4 and 5). The redistribution of support to permanent grassland (options 4 and 5) also contributes positively to the income of these farmers. In option 5, the redistribution of direct payments to smaller farms benefits to sheep farmers but affects negatively the income of cattle producers (on average 50% larger than the EU average professional farm). However, thanks to the redistribution of support to permanent grassland and to the coupled support to extensive livestock the fall in income is less drastic.

|

Graph 2.1 Impact of a 10% linear cut in support relative to baseline on EU income by type of farming

|

Graph 2.2 Impact of a shift in priorities applying on top of a support cut on EU income by type of farming

|

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP, changes relative to option 1

|

For milk producers, the average impact is relatively lower; though it hides significant differences between production systems. Very extensive systems grass-fed have high income drops in options 3a and 5 and the reduction in income of most intensive farmers varies between 8% in option 3b and 14% in option 5. The income effects assessed in this analysis for pigmeat and poultry producers derive mainly from the changes in support and practises for arable land. 70% of pigs and 45% of poultry are produced on farms with more than 10 ha.

The income of olive producers, largely depending on direct payments and often granted higher per hectare payments, drops significantly in all options, except in option 5 because olive growers are on average 65% smaller than the average EU farm. Changes in income of wine and fruits (orchards) producers are smaller, because, first, the share of direct payments in income is lower and, second, the simulated changes in farm practises related to permanent crops are less constraining (i.e. the adoption costs of permanent cover crop is relatively low compared to income.

The reduction and redistribution of direct payments, as well as the higher requirements to increase environmental benefits affect COP (cereal, oilseed and protein crop) producers in all options in 'normal' years. The negative impact on producers of other field crops is amplified by the crop rotation obligation and by the removal of coupled support to sugar beet in almost all options.

The cut in direct support (options 1 and 3) has a strong effect on crop producers because direct payments represent a large share of their income, 10% lower direct payments imply an income drop by 6% for specialised COP producers. In addition, in all options (except option 3b), direct payments are regionalised. It implies that in MS where the per hectare direct payment level still varies between farmers (mainly in relation to historic references), the income of COP farmers which traditionally received higher per ha payments is negatively affected by the introduction of flat rates (whether at MS level or by land type). In option 4, the redistribution of support to permanent grassland (with the unitary level increased by 20%) implies little changes in per hectare payment for arable crops in MS with arable area significantly larger than grassland in DK, while in DE and FR it leads to a drop by more than 5% and in the Netherlands by 20%.

Significant changes in land allocation to be expected

Conditionality requirements have a significant impact on crop producers notably in MS with a lower share of fallow land (12 MS have less than 2% of UAA with fallow land, see Annex 5.4). On average in the EU, in option 4b and 5 where only minimum requirements (3% of UAA with non-productive elements) apply, the share of fallow land and set aside in UAA increases by around 1 percentage point (pp) and by more than 2 pp in option 3a and 4a, where MS implement more ambitious green requirements. However, this effect is overestimated because of the lack of knowledge on landscape elements. To limit this overestimation, the requirement was modelled as the obligation to keep non-productive elements on 3% of the arable and permanent crop area (assuming that more linear elements are present on permanent grassland). This is one of the explanatory factors of the significant increase in permanent grassland simulated by the model (up to +4.5% in option 3a and 4a). Though overestimated, it shows that increased requirements could be an incentive for farmers not to plough temporary grassland.

The crop rotation obligation implies a switch from more remunerative activities such as horticulture and others field crops to less remunerative activities such as soft wheat, oilseeds and set aside. The difference in income drop between option 4a and option 4b can be directly interpreted as the effect of enhanced conditionality (modelled here as winter soil cover with catch crops, 3 year rotation and the obligation to have 2% more of UAA with non-productive elements). The simulated income drop is above 15% for potato and sugar beet producers and close to 10% for COP producers. The crop rotation obligation leads more particularly to a decline in grain maize, durum wheat, sugar beet and potato areas. In this simulation, the income drop is also high for horticulture because in the model farmers producing only vegetables in open field can rotate only between tomatoes and other vegetables, while in reality the diversity of vegetables at hand of farmers is wider. The 2-year rotation does not lead to a decline in soft wheat area; on the contrary it increases in option 3b (+2% relative to option 1). For soft wheat, the 3-year rotation might play a role but a stronger factor is the drop in support; it can be seen in option 5 where the redistribution of direct payments to smaller farms (while COP producers are on average more than twice larger than the average EU farm) and to other production systems (organic, permanent grassland, hedges and areas with natural constraints - ANCs) leads to a 5% wheat area decline and contributes strongly to the 14% drop in income of COP producers relative to option 1.

The fact that COP farms tend to be larger explains also why farms subject to capping of support are mainly specialised in crop production.

The increase in oilseeds area derives mainly from the 3-year rotation obligation (options 3a and 4a), while the decline in protein crops derives from the removal of coupled support (option 3a, 4a and 4b) as well as the fact that nitrogen-fixing crops do not qualify either to fulfil conditionality requirements nor for the ecological focus area requirements set by MS with high green ambition (option 3a and 4a). The top-up simulated in option 5 (80 EUR/ha) implies an increase of pulses area by 44% relative to option 1, which is quite significant even though protein area is still small in the EU. It shows the positive effect on production of coupled payments for this crop with lower economic profitability.

Table 2.2 Changes in land allocation due to changes in support and green requirements (%)

|

|

Cereals

|

Oilseeds

|

Protein crops

|

Sugar beet

|

Potato

|

Set aside and fallow land

|

Permanent grassland

|

|

Relative to baseline

|

|

1

|

0.1%

|

-0.1%

|

0.3%

|

-0.6%

|

0.0%

|

0.1%

|

0.0%

|

|

Relative to option 1

|

|

3a

|

-6%

|

5%

|

-23%

|

-23%

|

-10%

|

37%

|

4.5%

|

|

3b

|

-2%

|

1%

|

-12%

|

-8%

|

-2%

|

10%

|

3.7%

|

|

4a

|

-7%

|

6%

|

-9%

|

-23%

|

-10%

|

34%

|

4.5%

|

|

4b

|

-3%

|

-2%

|

-17%

|

-12%

|

-2%

|

19%

|

3.7%

|

|

5

|

-7%

|

6%

|

44%

|

-13%

|

-3%

|

15%

|

3.7%

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP, % changes based on FADN data covering 90% of EU land.

Table 2.3 Changes in land allocation applied to the 2030 EU agricultural outlook (1 000 ha)

|

|

Cereals

|

Oilseeds

|

Pulses

|

Sugar beet

|

Potato

|

Set aside and fallow land

|

Permanent grassland

|

|

1

|

100

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

3a

|

-3 400

|

600

|

-300

|

-400

|

-100

|

2 000

|

3 400

|

|

3b

|

-1 100

|

100

|

-200

|

-100

|

0

|

600

|

2 800

|

|

4a

|

-4 000

|

700

|

-100

|

-400

|

-100

|

1 900

|

3 400

|

|

4b

|

-1 700

|

-200

|

-300

|

-200

|

0

|

1 000

|

2 800

|

|

5

|

-4 000

|

700

|

700

|

-200

|

0

|

800

|

2 800

|

Source: DG AGRI

The changes in land allocation resulting from the other model used in this analysis (CAPRI) are smaller, especially for cereals, but indicate broadly the same trends. In addition, in CAPRI contrary to IFM-CAP, land abandonment is accounted for. All options result in a small reduction in UAA: 300 000 ha because of the budget cut and on top around 500 000 ha less in option 4a (-0.3% compared to option 1) and 400 000 ha in option 3a where more requirements apply. The decline is smaller in options 3b and 4b (260 000 ha and 200 000 ha respectively), while in option 5, the UAA remains almost stable compared to option 1. In IFM-CAP, the UAA is assumed to be fixed in all scenarios.

The targeting of direct payments is significantly improved in options 4 and 5

The options test various ways of targeting direct payments and CAP support:

·to smaller and medium size farms via a payment level modulated by size (option 5), a redistributive payment (option 3b) and a capping system which all allow accounting for the economies of scale in larger farms.

·to farmers most in need via the support to areas with natural constraints, coupled support to extensive livestock, the redistribution of support to permanent grassland (allowing indirectly to target farmers with lower income in option 5).

·to incentivise farm practices more beneficial to the environment, climate and health, via conditionality, the eco-scheme and environmental top ups.

Targeting support to small and medium size farms

Note: This assessment was carried out with the IFM-CAP model, based on FADN representing commercial farms. These farms are on average larger than the whole farm population. In FADN, EU farms have on average 30 ha, accounting for all farms, the average farm size drops to 16 ha (farm structure survey 2013).

The modulation of the basic decoupled payment by size is an efficient way to redistribute support from larger to smaller and medium size farms in physical and economic terms currently receiving less support (option 5) and can almost fully offset the effect of budget cuts on farms with between 5 and 30 ha. However, the modulation simulated here implies a close to 30% reduction in support to farms with more than 500 ha and an income drop above 10%, while these farms employ more people (20 AWU on average, 13 times more than the EU average). The redistributive payment simulated in option 3b (80 EUR/ha from 2 to 30 ha) allows also a shift of support to smaller farms, with lower income drops for larger farms though.

Importantly, the increase in minimum requirements to be eligible to decoupled payments leads to a lower support granted to farms with less than 5 ha in option 3 and 4 (see also chapter 2.1.3). This percentage is particularly high (between -25% and -33%) because the support granted to these farms in absolute value is small (around 1 000 EUR/farm in option 1). In addition, farms below 5 ha can have a large economic size and higher income than average (wine, horticulture). Therefore, in terms of economic size, the change in support for smallest farms is lower (-15% in option 3a to -6% in option 4).

|

Graph 2.3 Change in support relative to option 1 by area size class (ha)

|

Graph 2.4 Change in support relative to option 1 by economic size class (1 000 EUR)

|

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

Note: direct payments include the basic decoupled payment, the redistributive payment and coupled support. Total support includes the eco-scheme, the environmental top ups, the ANC payment and the agri-environment-climate measures.

The redistribution simulated in option 4 implies higher support to farms above 150 ha, because of the increased support to permanent grassland. However, this regionalisation by land type is efficient in shifting direct payments from more intensive farms to more extensive ones (

Graph 2.6

). In option 5, the higher direct payments granted to first hectares imply a relatively lower decline in basic payment to most intensive farms (smaller on average) and a decline to most extensive ones. The latter effect is compensated with coupled support to extensive livestock and top ups to permanent grassland.

Targeting support to farmers most in need (with lower income)

The current policy is granting higher support to farms with higher income but also to the 10% farms with the lowest income (

Graph 2.5

): the latter receive 8 000 EUR/AWU, the 50% farms with the highest income receives around 12 000 EUR/AWU relative to between 2 000 and 6 000 EUR/AWU for the other farmers.

None of the options perform better than the baseline, because redistributive effects do not offset cuts and some support is re-allocated to risk management. Option 5 (decoupled payment modulation by size, coupled support for extensive livestock and top-up to permanent grassland and ANC) performs as well as option 1 to redistribute support from farms with higher income per AWU to those with lower income level. Option 4 (regionalisation by land type and redistribution to permanent grassland) performs slightly less. Provided farmers will largely adopt the voluntary eco-scheme to catch the premium, option 3b (redistributive payment) would perform as well as option 4. In any case, mainly because of the reallocation of support to risk management option 3a performs the least.

|

Graph 2.5 Support per AWU by class of income (Q1 = lower to Q10 = higher income)

|

Graph 2.6 Change in support relative to option 1 by class of production intensity

(Q1 = more extensive to Q10 = more intensive income)

|

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

In option 3a this shift in priorities affects negatively almost equally farmers of all economic classes. Option 3b with the redistributive payment allows maintaining the income of medium economic size farms (from 8 to 100 000 EUR) while support drops is higher for larger farms. In addition, would the uptake of eco-scheme be lower, support drops could be larger.

It is a well-known phenomenon that some years the farm net value added of farms is negative (market revenue + subsidies – total costs – depreciation), it does not mean that the cash flow is negative but that accounting for the loss of capital value the farm income is negative. If this situation lasts for several years it is threatening strongly the viability of the farm.

Table 2.4 Share of farms with negative income

|

Baseline

|

1

|

3a

|

3b

|

4a

|

4b

|

5

|

|

14%

|

15%

|

17%

|

15%

|

16%

|

15%

|

15%

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

In the baseline, the share of farms with a negative farm net value added reaches 14%, this share increases to 15% in option 1 with the budget cut. In option 3a, with the shift of priority to risk management tools and the increased environmental-climatic ambition this percentage increases to 17%. In option 4b, the loss in revenue due to the same environment-climate ambition leads to 16% of farms with negative income. In the other options (3b, 4b and 5), the share is the same as in option 1.

It is important to note once more that structural change is not accounted here. But in a situation of income deterioration an increase of the number of farmers leaving the agricultural business might be expected. In addition, in this modelling exercise only intermediate costs vary with the changes in farming practices but fixed costs (labour, machinery, energy…) remain constant, while some adaptation might take place too.

A fairer distribution of support

Capping the level of DP farmers can be granted is seen as one way to reach a fairer distribution of support. In this simulation, two levels of capping per farm were tested: 100 000 EUR (options 3 and 4) and 60 000 EUR (option 5). In this impact assessment, only the capping of the basic payment and the redistributive payment were simulated. Elements changing across options (the eco-scheme, the environmental top-ups and the coupled support implemented to address EU concerns and sectors in difficulty) were not part of capping, to facilitate comparison across options.

Currently, only 8 MS apply a capping from a threshold of 150 000 EUR to 500 000 EUR. In addition, direct payments are cut (by 5% to 50%) from 150 000 EUR per farm in 14 MS. It raises a capping product of 120 million EUR, coming mainly from HU, PL and BG. The capped farms have close to 50 employees on average (see Annex 5.5). It means that the current capping penalises farms providing numerous jobs. Despite the possibility to apply a correction for salaries HU, PL, SK and CZ do not apply it, because it is deemed too complicated. Lowering the capping threshold to 100 000 EUR or even 60 000 EUR could convince these MS to apply this correction, even to possibly consider family labour. It could also be looked at a simpler solution to deduct salaries, possibly based on MS average wage. In addition, with a capping level at 60 000 EUR the possibility to deduct opportunity costs for family labour could as well be considered.

Applying a capping of 100 000 EUR (with salaries correction) to the current basic decoupled payments (BPS/SAPS and greening) ceteris paribus would raise a capping product of 350 million EUR. Applied to all direct payments the capping amount could reach 920 million EUR. However, the budget cut and the shift in priorities could lead to much lower capping products: 0 EUR in option 3a (where the basic payment represents only 25% of pillar I envelope), 10 million EUR in option 3b, 50 million EUR in option 5 (despite a capping at 60 000 EUR).

In addition, in all capping scenarios, BG and RO are the 2 MS where most of the direct payments are capped, despite the correction of salaries. In HU, CZ and SK the salaries correction implies a strong drop in capped amounts. Would capped amounts be cut from MS envelopes it would raise a serious issue of cohesion, knowing that these two MS grant among the lowest support per ha and belong to the poorest MS of the EU.

This is why, in option 4, the capping is used as an actual tool of redistribution. Meaning that instead of cutting the envelope (by potentially more than 300 million EUR, out of which more than 60% in BG and RO), the budget is redistributed to smaller farmers by increasing the per hectare payment (by around 10% in BG and 6% in RO). It is not a simple budgetary mechanism but it addresses citizen concerns without damaging cohesion.

In the option where the link to historic payment levels is kept (option 3b), on top of the capping per farm, a capping per ha was introduced (1 000 EUR/ha of basic payment and redistributive payment in this simulation). The number of farmers affected is relatively low compared to how many farmers would have been affected if that capping would have applied in 2015. The main reasons are: the increasing convergence of direct payments per ha to take place in the coming years and accounted for in the baseline, the reduction of direct payments simulated in option 3b and the potential lack of representativeness of these farms in FADN. An assessment carried out on the 2015 payments (CATS database) showed that a capping per ha of the basic payment scheme, the single area payment scheme and the greening at 1 000 EUR/ha would have led to cut direct payments to more than 200 000 beneficiaries and to a capped amount of 1.5 billion EUR. The farms capped are mainly located in EL, IT and ES. They have an average of 4 hectares and received around 7 400 EUR per farm in 2015. Most of these farmers are olive growers but there are also some intensive livestock producers (cattle and sheep). With a capping at 600 EUR/ha, the number of beneficiaries capped would have raised to 600 000 and PT would be hit too. A capping level relative to the average direct payment per MS was tested too and revealed more proportionate.

Table 2.5 Capped amounts by option

|

|

Baseline

|

Baseline+capping

|

3a

|

3b

|

4

|

5

|

|

Level of capping

|

various

|

100 000

|

100 000

|

100 000

|

100 000

|

100 000

|

60 000

|

|

Scope

|

BPS/SAPS

|

BPS/SAPS + greening

|

all DP

|

BP

|

BP and redistributive payment

|

BP

|

BP

|

|

Product of capping (MEUR)

|

120

|

350

|

920

|

0

|

10

|

0

|

50

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

Capping is not the most efficient way to reduce the concentration of direct payments, when the funding no longer paid to large farms is removed from the direct payments budget altogether instead of being redistributed to smaller farms. Modulation of direct payments by size is more effective to reduce the share of direct payments received by the 20% biggest CAP beneficiaries as illustrated in the graphic below. In option 5, these beneficiaries capture 67% of direct payments, relative to 73% in the baseline

. This reduction might seem small in view of the huge redistribution to small and medium farms operated in option 5, however it highlights that support concentration derives from land distribution in the EU. Option 3b, allows for a drop in concentration of 2 pp only thanks to the redistributive payment. By contrast, options 3a and 4 imply a small increase in concentration of DP.

However, some of the large beneficiaries employ a lot of people, looking at the concentration of direct payments not by beneficiary but by worker, the level of concentration reduces to 66% for the 20% of farm labour employed on farms with largest direct payments per AWU in the baseline. In option 5, this concentration is 3 pp below.

Graph 2.7 Share of direct payments received by 20% farms

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

Another measurement of support concentration is the Gini coefficient, varying between 0 and 1: the closer to 0 the lower the concentration. In the EU, the Gini coefficient of land concentration (again measured using the FADN sample) is 0.58, not surprisingly very close but slightly below the concentration of support in the baseline at 0.57. As concluded based on the measurement of the share of direct payments granted to 20% of biggest beneficiaries, option 5 allows for a reduction in support concentration (Gini coefficient of 0.55), while the concentration increases slightly in option 3b and 4 and more significantly in option 3a (0.61) due to the flat rate payments. In terms of income, the budget cut leads to a higher concentration of income (option 1, 0.735) relative to baseline (0.729). None of the tested options allows correcting this; on the contrary, as for support, options 4a and 3a imply a higher concentration of income in the hand of more efficient farmers in terms of income generation. The difference in Gini coefficient between option 4a and 4b shows the effect of the higher environmental-climatic ambition simulated here: the losses in market revenue implied by changes in farm practices slightly increases income concentration.

Table 2.6 Concentration of land, direct payments and income measured with a Gini coefficient

|

|

UAA

|

Direct payments

|

Income

|

|

Baseline

|

0.579

|

0.570

|

0.729

|

|

1

|

|

0.570

|

0.735

|

|

3a

|

|

0.609

|

0.750

|

|

3b

|

|

0.575

|

0.739

|

|

4a

|

|

0.581

|

0.745

|

|

4b

|

|

0.581

|

0.738

|

|

5

|

|

0.552

|

0.739

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP, based on professional farms (FADN data)

2.1.2.Reduce inequalities between territories by supporting farms across the whole territory

Historically, direct payments granted to areas with natural constraints were lower and this gap was compensated by a specific aid to ANCs, programmed in rural development. The area in ANCs represents around 50% of EU area and 30% of the eligible area. In the baseline, farms in mountain areas are granted around 6 500 EUR of direct payments per farm while outside ANCs farms are granted around 8 400 EUR. Accounting for ANC support but also agri-environmental payments the average support increases to more than 10 000 EUR granted in mountain areas and around 9 000 EUR outside ANCs.

The share of pillar II envelope dedicated to ANCs is 17% in the current programming period. In all options, support to ANCs is maintained given the importance to keep farms on the whole EU territory to support employment in rural areas and also for the environmental benefits associated with farming activity. However, some MS dedicate a very large share of their rural development envelope, (especially France 37%, Ireland and Finland 32% and 29% in Luxembourg ), meaning that in a context of reduced EU budget and of gaining importance of other priorities, to continue supporting farms in ANCs at the same level, MS might need to use additional national funds (as simulated here in option 3b for all MS and in option 4 where a maximum of 25% of pillar II envelope for ANC is tested implying a reduction in EU funds for ANCs in FR, IE, LU, CZ, SK, SI and SE).

In option 1, the budget cut implies a 10% reduction in support in ANCs. In option 3, provided ANC payments are maintained, total support in ANCs could remain equivalent to option 1, but support in less favoured areas not mountain would decrease further.

By contrast, option 4 by redistributing support to permanent grassland re-directs support to mountain areas but the most efficient way to support mountain areas is a specific top up granted in pillar I to ANC as in option 5 (provided farmers could keep the same level of aid in MS granting large national support to ANCs). However, in both options ANCs not located in mountain areas do not benefit from reallocation of support.

|

Graph 2.8 Change in support relative to option 1 by ANC zone

|

Graph 2.9 Income per AWU by ANC zone

|

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

|

2.1.3.Simplify increasing thresholds to receive decoupled payments

In order to reduce the number of beneficiaries of very small amounts of aid, deemed not contributing significantly to farmers’ income, thresholds apply currently. MS fix them in euros (varying from 100 to 500 EUR) and/or in hectares (varying from 0.5 to 5 ha). In this analysis, the introduction of a 2 hectares threshold is tested (option 3). This option would exclude from the direct payment system more farmers than the current system (options 1 and 5) and then a system based on thresholds in EUR accounting for the differences in standard of living (option 4).

An analysis based on the 2016 CAP beneficiaries shows that a 2 hectares threshold would have reduced the number of beneficiaries by than 1.5 million (24%) for a reduction in hectares paid by 1.3% only, 3% of the amount of basic payment, single area payment and small farmer scheme granted and 2% of total direct payments paid. These beneficiaries were granted on average 420 EUR in 2016. This amount varies between 85 EUR in LT to close to 3 300 EUR in NL (where the flat rate will apply from 2019 only).

A threshold at 2 ha might be too high in MT and CY where around 70% of beneficiaries fall under the threshold and are granted more than 40% of basic decoupled payments in MT and around 15% in CY. Similarly, large share of payments were granted to beneficiaries with less than 2 ha in 2016 in EL (15%), RO (10%), IT and PT (7%). However, this threshold could represent a real simplification in MS such as BG, SK, HU and LT where more than 15% of beneficiaries are granted less than 1% of the payments. A question remains about the importance of the aid contribution (around 80 EUR in LT, 200 in BG and in SK, 400 in HU) to these farmers’ income.

Option 4 is testing a threshold in EUR, above the current thresholds applied, and corresponding to the equivalent of 2% of agricultural income. It means that to receive basic decoupled payments, farmers need to be eligible to a minimum of basic decoupled payment varying between 100 EUR (in RO, BG, PL, HR, SI) and 1 000 EUR in DK. Applied in 2016, such a system would have reduced the number of beneficiaries by 10% (0.6 million) and the amount of aid paid by 0.7% only and an average amount of 240 EUR granted per beneficiary. With a threshold at 200 EUR more than 60% of Maltese farmers would fall out of the direct payment system for a 33% share of basic decoupled payments. In the other MS, the share of payments granted to beneficiaries below the thresholds is smaller: 5% in CY, 4% in LT and 3% in IT.

A threshold in euros, can avoid excluding from the system potential beneficiaries of amounts of aid important for the living of farmers. However, a threshold in hectares is much simpler to manage than a threshold in euros, for which the calculation of payments needs to be done before beneficiaries can be excluded. MS could explore further the most adequate threshold level. In addition, in context of reduced direct payments the amounts of aid granted to beneficiaries below 2 ha would be smaller.

Table 2.7 Beneficiaries below tested thresholds in 2016

|

million

|

Beneficiaries

|

Area paid

|

Amount paid

|

|

Total in 2016

|

6.5

|

154

|

23 069

|

|

of which below 2 ha

|

1.5

|

1.9

|

640

|

|

|

24%

|

1.3%

|

2.8%

|

|

of which below 2% of ag. Income

|

0.6

|

1.2

|

152

|

|

|

10%

|

0.8%

|

0.7%

|

Source: DG AGRI, CATS, based on BPS, SAPS and SFS

To assess better who are the beneficiaries potentially excluded from direct payments with various thresholds, the analysis was run with the IFM-CAP model. Given it is based on FADN surveying only professional farms, the number of beneficiaries below thresholds is smaller.

In the baseline, farmers below threshold are many involved in wine production and horticulture, they are located at more than 30% in ES and also in RO, IT and FR. Some of them have a very large economic size (12% with more than 100 000 EUR of size). Would these farms have been granted direct payments their income would have increased by less than 1% for most types of farming.

As shown based on the 2016 payments, option 3 leads to a higher number of farmers excluded from the direct payments system. The reduction by half of the number of farmers below thresholds in option 5 compared to baseline, highlights the impact of the reduction in direct payments and at the same time the increased payments to smaller farms. This is why the number (and share) of farms below threshold from the lower economic class increases in this option.

In option 3, farms below thresholds are mainly mixed farms, located in RO and IT and of the smallest economic size. In option 4, the distribution of farms below thresholds by type is close to the baseline situation, with a higher share of sheep and dairy farms and RO though. In option 4, the number of farms below thresholds is lower than in option 3 but the impact on farms income is slightly higher, though rather low (estimated at 1% against 0.7% in option 3b). These thresholds would weigh more cattle producers with low income in option 4 and on olive producers in options 3 and 4.

Table 2.8 Identification of professional farms below thresholds

|

|

Baseline

|

Option 3

|

Option 4

|

Option 5

|

|

Total number of farms

|

285 800

|

506 000

|

322 100

|

134 000

|

|

Change/baseline

|

|

77%

|

13%

|

-53%

|

|

Share by specialisation

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

Horticulture

|

25%

|

19%

|

22%

|

29%

|

|

Wine

|

21%

|

12%

|

15%

|

16%

|

|

Mixed

|

19%

|

27%

|

24%

|

26%

|

|

Orchards

|

15%

|

10%

|

10%

|

7%

|

|

Sheep&Goat

|

4%

|

9%

|

8%

|

6%

|

|

Milk

|

2%

|

8%

|

7%

|

4%

|

|

Other

|

14%

|

16%

|

14%

|

13%

|

|

Share by MS

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

ES

|

34%

|

6%

|

12%

|

14%

|

|

RO

|

20%

|

40%

|

36%

|

29%

|

|

IT

|

18%

|

22%

|

24%

|

16%

|

|

FR

|

12%

|

6%

|

11%

|

16%

|

|

BG

|

6%

|

6%

|

3%

|

4%

|

|

EL

|

2%

|

8%

|

1%

|

3%

|

|

Other

|

9%

|

12%

|

13%

|

19%

|

|

LFA

|

42%

|

40%

|

42%

|

42%

|

|

Not LFA

|

58%

|

60%

|

58%

|

58%

|

|

Share by size

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

100%

|

|

2 - 8 000 EUR

|

37%

|

62%

|

53%

|

47%

|

|

8 - 25 000 EUR

|

31%

|

22%

|

23%

|

23%

|

|

25 - 100 000 EUR

|

20%

|

12%

|

16%

|

21%

|

|

> 100 000 EUR

|

12%

|

5%

|

8%

|

9%

|

Source: JRC, IFM-CAP

The small farmer scheme, which was introduced in the last reform as a simplified way to grant direct payments to smaller beneficiaries is not retained in the options because it is simpler for beneficiaries (thanks to the greening exemption notably) but not for the administrations.

2.1.4.Cope with price volatility and improve risk management

The 2014 US Farm Bill introduced a system with risk-based (countercyclical) payments. In the public debate this system was sometimes referred to as being more adequate compared to the EU system with direct payments complemented by risk management schemes. In order to evaluate its impact, an analysis with the Aglink-Cosimo model was performed assuming the CAP to adopt some of the programs of the US Farm Bill 2014. For a comprehensive description of the US Farm Bill 2014 we refer to the USDA Farm Service Agency. Specifically, two of the US Farm Bill 2014 programs were considered: the acreage risk coverage (ARC), which is substantially a revenue-risk insurance, and the price loss coverage (PLC), which is an insurance against prices dropping below certain levels. The analysis solely focused on maize, barley and soft wheat. For the PLC program, payments are triggered when the market price is lower than an arbitrarily chosen reference price level. For the ARC program, payments are triggered when the farm revenue goes below a specific revenue of reference, which in the US can be farm- or county-specific.

Graph 2.10 Deterministic results for baseline and three scenarios for EU total ARC and PLC payments (in 1 000 EUR)

Source: JRC, AGLINK-COSIMO

The analysis shows ARC payments in the order of approximately half a billion € in the worst years for the average set of reference prices. For the highest set of reference price levels the payments are in all 10 years above 1 billion €. A similar picture but with much higher absolute levels in monetary terms is shown for the PLC program payments at the EU-wide level. In this case there is a one-to-one correspondence between market prices being below the reference levels and the payments. Every time the market price is below the reference level, the PLC payments are triggered. This is not the same as in the ARC payments, where there is a simulated distribution of farmers' revenues and the benchmark revenue to trigger payments is the multiplication of Olympic averages of market price and yield. No PLC payments are expected if the low reference prices are chosen and medium reference prices trigger payments up to 5 billion € in the year 2019 when lowest prices are projected in the Outlook for the three crops considered under the ARC and PLC programs. High reference prices trigger PLC payments of 14 billion € for the 3 crops considered. For the ARC and PLC combined, with high reference prices, payments in the worst case scenario exceed 15 billion €.

The main conclusions are hence that a system based on risk-based payments creates significant budget uncertainty and presents a real danger for budget overshoot, depending on the chosen reference prices in relation to market developments. Note that the presented analysis only covers three crops. Furthermore, a system based on risk-based payments also does not sufficiently transmit market signals to farmers, as downward price pressure is cushioned, removing the incentive to adapt production to changing demand and can lead to overproduction.

The market orientation of the CAP has significantly increased over time and at the same time the exposure to world markets. In a context of climate change and higher occurrence of extreme events, farmers’ exposure to yield, price and income variability will increase. Thus, the proposed increase in financial means dedicated to risk management tools in option 3a (10% of pillar I) and options 3b and 4 (5% of pillar I), while option 5 remains status quo. Currently the uptake of risk management tools is rather low also because farmers count on direct payments to buffer income changes, but simulated budget cuts and the shift in priorities towards less income support (option 3) might increase farmers’ willingness to adopt these tools.

Based on FADN data, between 2007 and 2015, on average annually 30% farmers had a 20% or larger drop in sector income compared to the three previous years and 25% of EU farmers had a 30% drop in gross farm income (see Annex 5.7). Would an income stabilisation tool be available for all farmers, an EU budget between 13 and 15 billion EUR would have been necessary annually to compensate farmers. It is far more than the budget foreseen in options 3 and 4. Anyhow, the level of organisation required to set up a mutual fund to manage an IST imply that most probably only larger farmers would opt for that solution (also because for smaller farmers the main preoccupation might be their income level – better addressed with direct payments – rather than its variability). If only farmers with an economic size above 50 000 EUR would opt for an IST, the budget need could be almost divided by two. This would require nevertheless a larger budget than available.

MS are given the possibility to set up the IST for specific sectors, in the framework of the strategic plan. This provides an opportunity for MS to target sectors facing some years huge drops in income and for which other risk management tools are less available. For example, risk management tools are less developed in the livestock sector than for crops. Crop futures are well functioning and available to farmers but also to insurers to cover/hedge their risks, thus the wider availability of insurance products (which can be supported with EU funds too). By contrast, in the dairy sector, the volume traded on futures is still small (though increasing) and an IST could be of interest to farmers to protect themselves against market uncertainty. In other sectors, where the first issue in income level (beef and sheep for example), direct payments (included coupled support) can be best suited to support farmers.

Table 2.9 Estimation of annual compensation needs for an IST in the EU

|

|

|

MEUR

|

|

Envelope made available for risk management tools

|

Option 3a

|

3 400

|

|

|

Option 3b&4

|

1 700

|

|

EU compensation required if IST for all farmers

|

Farm income, 30% drop

|

13 300

|

|

|

Sector income, 20% drop

|

14 900

|

|

Compensation required if IST for larger farmers (> 50 000 EUR of size)

|

Farm income, 30% drop

|

7 200

|

|

Compensation required if IST for selected sectors (Sector income, 20% drop)

|

Milk

|

1 300

|

|

|

COP

|

2 600

|

|

|

Sugar beet

|

200

|

|

|

Olive

|

600

|

|

|

Pig&poultry

|

1 400

|

Source: DG AGRI, AidsK, FADN data

2.1.5.Competitiveness

The options assessed here imply little change in the competitive position of the EU in terms of price competitiveness. Farmers opt for reducing production in view of lower expected returns and higher costs and the increase in production prices is very small. Therefore in all options, the relationship between costs and revenue remains more or less constant and farmers reduce their livestock (especially cattle, see above) and cereal area (grain maize and wheat).

Therefore a deterioration of the EU trade balance is to be expected, with increased imports of beef, sheep and poultry meat as well maize in almost all options and reduced exports of beef and wheat mainly. The trade of dairy products is not affected. The EU trade balance reduces most in option 4a and 3a, and then 3b and the lowest decline is simulated in options 4b and 5.

Table 2.10 Changes in trade by main commodity

|

|

Beef

|

Sheep meat

|

Poultry meat

|

Pigmeat

|

Cereals

|

Oilseeds

|

Oilcakes

|

|

|

Exports

|

Imports

|

Imports

|

Exports

|

Imports

|

Exports

|

Exports

|

Imports

|

Imports

|

Imports

|

|

3a

|

-13%

|

20%

|

8%

|

-2%

|

2%

|

-3%

|

0%

|

1%

|

1%

|

-2%

|

|

3b

|

-3%

|

4%

|

3%

|

-1%

|

1%

|

-2%

|

-3%

|

6%

|

0%

|

0%

|

|

4a

|

-9%

|

13%

|

2%

|

-2%

|

3%

|

-4%

|

-1%

|

3%

|

1%

|

-1%

|

|

4b

|

-7%

|

9%

|

1%

|

-1%

|

1%

|

-1%

|

0%

|

-1%

|

0%

|

-1%

|

|

5

|

-9%

|

13%

|

-6%

|

-1%

|

1%

|

-1%

|

-1%

|

1%

|

0%

|

-1%

|

Source: JRC, CAPRI

2.1.6.Coupled support and competitiveness

Where the market fails to remunerate farmers for all the services they provide and where the lack of support could lead to land abandonment and closed landscapes (e.g. for extensive livestock in grassland areas) a coupled payment can be justified to help maintaining production in territories and sectors at risk.

The table below highlights the impact on production, productivity and prices of removing coupled support (in isolation from other changes) compared to the baseline: a decrease in area and herd, an increase in productivity (dairy and sugar beet) mitigating production effects, as well as a price increases.

Table 2.11 Changes in price and production would coupled support be fully removed

|

|

Hectares or herd size

|

Yield

|

Supply

|

Price

|

|

Dairy

|

-0.7%

|

1.5%

|

0.7%

|

1.4%

|

|

Beef

|

-2.5%

|

0.2%

|

-2.4%

|

3.2%

|

|

Sugar Beet

|

-4.9%

|

2.2%

|

-2.8%

|

3.9%

|

Source: JRC, CAPRI

Coupled support has implications on the level playing field in the EU, because of the differences in implementation between MS, it might lead to unfair competition and to an increase in production. In addition, the World Bank in a recently published study, points out that coupled support prevents productivity increases contrary to decoupled and pillar II payments. The results also show that yield gains would have been higher without support for milk and sugar beet.

The voluntary coupled support, as currently implemented, addresses only in part EU concerns: close to 70% of the support is granted to the sheep, cattle and protein crop sectors. The targeting could be further improved by limiting support to extensive livestock providing positive amenities as proposed in options 4 and 5. For the rest of the coupled support currently granted, several issues can be pointed out:

·A lack of targeting: in the dairy sector for example, in several MS a large share of dairy cows are eligible, sometimes to small amounts (like in FR and BE, below 30 EUR/head) questioning the usefulness of the scheme and sometimes to large amounts (like in CZ and HU) questioning in this case the proportionality of the scheme and the competitive advantage given to these producers. Similarly, in MS granting a coupled payment to sugar beet, generally all the area is eligible.

·An impact on production.

·A contradiction with a market oriented policy. The use of coupled support can be questioned when it is used, like in the sugar sector, to compensate for the lack of competitiveness of a whole country (and not a specific territory). Clearly, in such cases MS have put forward the social dimension of the support which helps keeping employment in the related processing industry, however without addressing the structural issue.

·Competition issues. Coupled support introduces elements of unfair competition between MS. This can be illustrated with the coupled support granted to the sugar sector, where the aid granted in 2015 reached from 100 EUR/ha in FI to 800 EUR/ha in RO. In other words, in RO sugar beet growers received a coupled support of 20 EUR/t, while e.g. in BE where no VCS was granted, sugar beet growers signed contracts at 23 EUR/t. In addition, the CAPRI analysis shows that without support, RO would have produced 53% less.

·Disproportionate unit amounts may be paid: this happens, in absence of any 'safeguard', when to avoid unspent funds MS increase the unitary level of aid when there is a drastically smaller number of applicants than planned.

However, coupled support can address specific issues that the decoupled payment would otherwise leave unresolved. Coupled support could be limited and granted to sectors identified by MS as undergoing certain difficulties. This is why in options 4 and 5, coupled support was introduced to address some EU concerns. In option 3b, the possibility to grant coupled support was extended to sectors identified by MS as particularly important for social, economic, or environmental reasons, undergoing certain difficulties with the view to overcome these difficulties after a certain number of years.

2.2.Increasing the environmental and climatic benefits of the CAP

It is proposed in the new green architecture to remove EU exemptions and thresholds. It implies that all the potentially eligible area will be under minimum conditionality. In addition, in the options where entitlements can be removed (all except option 3b), the area covered by payments could increase and thus the area under conditionality (currently the area granted an aid is below 90% of the UAA). However, in this modelling exercise some exemptions were introduced to avoid overestimating effects of some requirements.

2.2.1.Contribute to climate change mitigation & adaptation

Reduce GHG emissions

Previous analysis shows that there is a need to give a dedicated incentive to farmers in order to reduce GHG emissions. The ECAMPA project (see Box 1) showed that, in the absence of a compulsory emission reduction target for agriculture, a subsidy covering 80% of the costs of mitigation technologies, could deliver significant non-CO2 emission reductions, with little negative impact on EU production. However, this measure would come along with considerable budgetary and unitary costs if farmers are projected to widely adopt the technologies, estimated at around the current total pillar II envelope. The fact that such incentives are not explicitly included in the present analysis (also because of its budget-neutral assumption) explains why only small reductions in non CO2 emissions compared to baseline are reached in this assessment.

In addition, this assessment is an underestimation of potential GHG emissions reduction because the impacts of land use change and carbon sequestration are not fully captured in the CAPRI model. However, the model accounts for changes in livestock diets and for the adoption of some mitigation technologies. The potential impact of targeted measures and other effects to reduce GHG emissions that could not be covered by quantitative modelling were taken on board in the different options of the MCA analysis (section 3.2.4.1).

The budget cut (Post Brexit) implies a 0.1% reduction of GHG emissions compared to baseline. In addition, all options show a small decrease of non-CO2 GHG emissions, ranging between 0.6% and 1.6%. Between 34% (4b) and 50% (4a) of the reduction comes from direct N20 emissions from the application of mineral fertilisers, followed by 22% (4a) to 36% (4b) from methane emissions from enteric fermentation. Even though the difference in impact between the options in terms of non-CO2 GHG mitigation is a factor of three, this represents only between 2.6 and 7 million t CO2 eq/year.

The main drivers for the reduction in non-CO2 emissions are the introduction of a tool for nutrient management with reduction targets of N-surplus. As the reduction target of the NMP is higher in option 3a and 4a compared to the other options, it is quite logical that these scenarios show the biggest reductions in terms of GHG emissions.

Farmers may react to these reduction targets via production changes but also via the implementation of mitigation technologies. Around 56% of the total reduction in GHG emissions is achieved via mitigation technologies in option 4a, while it is around 25%-45% in the other options. The major part of the reduction is due to precision farming and the use of nitrification inhibitors out of four farming practices. The results show as well that there is no adoption of other mitigation technologies in absence of any other incentive directly targeting non-CO2 mitigation technologies. It should be noted that in the ECAMPA2 study (see also Box 1), a scenario with a subsidy covering 80% of the costs of mitigation technologies but no compulsory emission reduction target for agriculture, delivered about 13.5% of non-CO2 emission reductions by 2030 compared to 2005, with little negative impact on EU production.

Box 1: What's the potential of GHG emission mitigation in agriculture?

The options considered in this impact assessment do not include specific GHG emission reduction targets or policy obligations to mitigate GHG emissions from EU agriculture. While the possibility for uptake of emission mitigation technologies is considered in the quantitative analysis, adoption by farmers is low (see section 2.2.1), which explains why the GHG emissions reduction achieved in the different policy options is limited. This is in line with the main findings of the EcAMPA 2 study (Pérez Domínguez et al., 2016), which shows that adoption of mitigation technologies in the agricultural sector is unlikely to happen at a large scale without additional incentives.

In the EcAMPA 2 study, the role of emission targets and subsidies for the uptake of technological (i.e. technical and management-based) mitigation options was specifically addressed with the CAPRI model for year 2030. The study examined the impacts of policy instruments directly targeting non-CO2 GHG emission reductions in the EU agricultural sector, concluding that without further policy incentives, EU-28 agricultural GHG emissions would decrease by about 2.3 % by 2030 compared with 2005. EU agricultural production would be significantly reduced if the sector was to deliver a -20% emission reduction without including subsidies for the adoption of mitigation technologies. Livestock herds would be substantially affected, especially cattle for beef production. Negative production impacts of a mitigation target would be more limited if the implementation of emission mitigation technologies by farmers would be subsidised. Furthermore, the study showed that considerable emission reductions could also be achieved when including subsidies for emission technologies without a specific emission target. In this case, emissions would decrease by about 13.5% compared to 2005, without negative impacts for EU agricultural production. However, EcAMPA 2 showed that the subsidies payed in the scenarios would lead to additional budgetary costs between 12.7 and 15.6 billion EUR (188 - 278 EUR/t CO2 eq mitigated) depending on the scenario setting (i.e. voluntary vs. mandatory adoption modalities, cost and number of technologies available, etc.).

Graph 2.11: Contribution of each technology to total mitigation (EU-28, 2030)

Source: Pérez Domínguez et al. (2016). HET20 = Compulsory 20% mitigation target for EU-28 agriculture, cost-effective allocation by MS; SUB80V_20 = same as HET20, but with 80% subsidy for the voluntary application of mitigation

The positive effect of a reduction in GHG emissions is partly offset by emission leakage, meaning increased emissions outside the EU, to produce agricultural products to be imported into the EU or to replace EU exports. Between 35% and 75% of the GHG emission savings are substituted by additional emissions outside the EU (the so-called leakage). This effect is the strongest in option 3a due to the strong decline of EU beef production replaced by imports from less efficient regions in terms of GHG emissions/kg of product based on the historical emissions efficiency trends as the exact impact of the Paris Agreement in different parts of the world is yet unclear. In general, all measures that lead to production drops imply a reduction in gross GHG emissions. However, only a change in human consumption will translate into an actual reduction of GHG emissions worldwide (i.e. to avoid leakage).

These average results hide diverging impacts at national and regional level due to the prevailing farming systems in the baseline. Another explanatory element is the implementation of the tool for nutrient management assuming that regions with a high livestock density need to reduce the nitrogen surplus with a higher percentage than regions with a lower nitrogen surplus.

Table 2.12: Relative contribution of emission categories to total emission reduction (%) in the different options

|

|

3A

|

3B

|

4A

|

4B

|

5

|

|

N2O from application of manure

|

3

|

4

|

3

|

4

|

4

|

|

N2O from grazing animals

|

7

|

3

|

5

|

9

|

8

|

|

N2O from manure management

|

3

|

3

|

2

|

3

|

3

|

|

N2O from application of mineral fertilisers

|

40

|

43

|

50

|

34

|

36

|

|

N2O from organic soils

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

0

|

4

|

|

N2O from crop residues

|

4

|

12

|

4

|

6

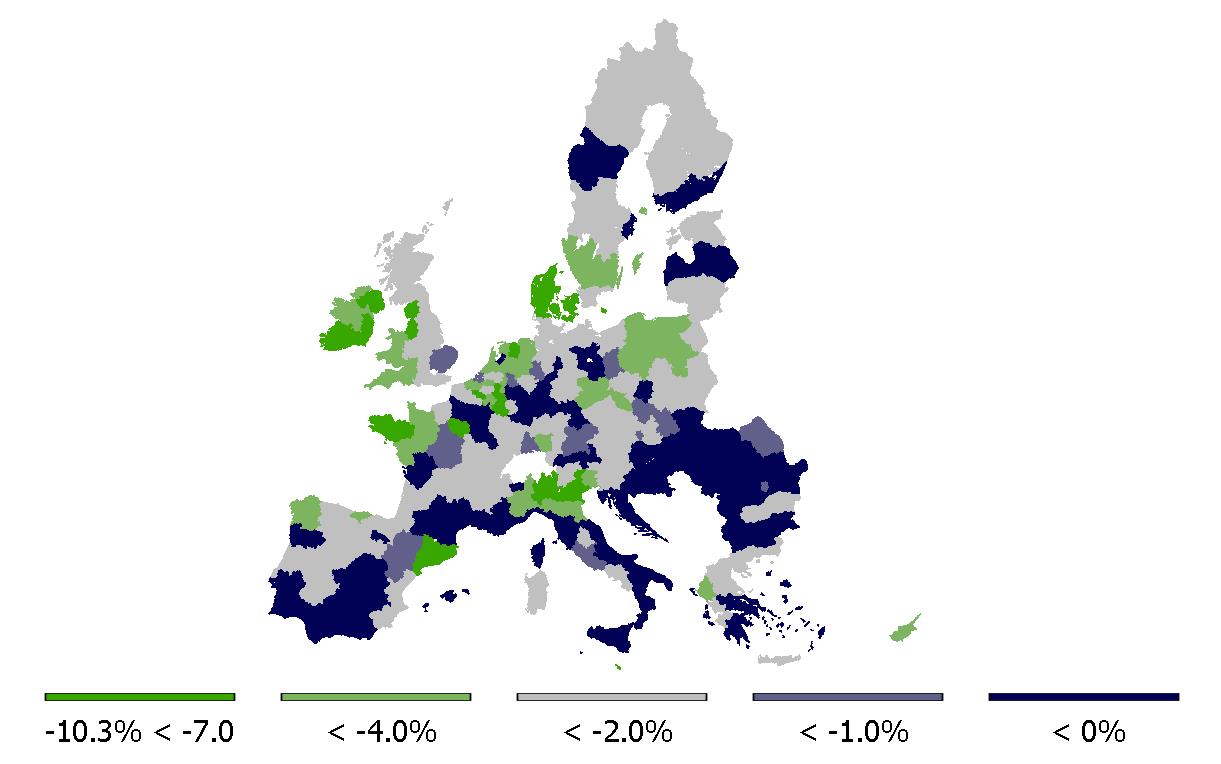

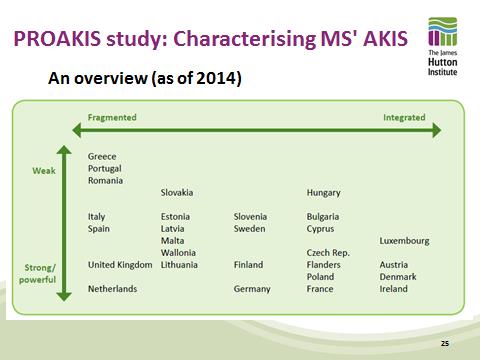

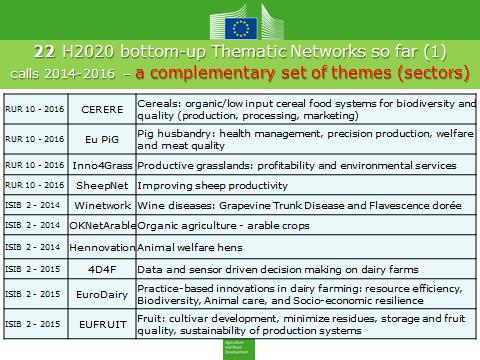

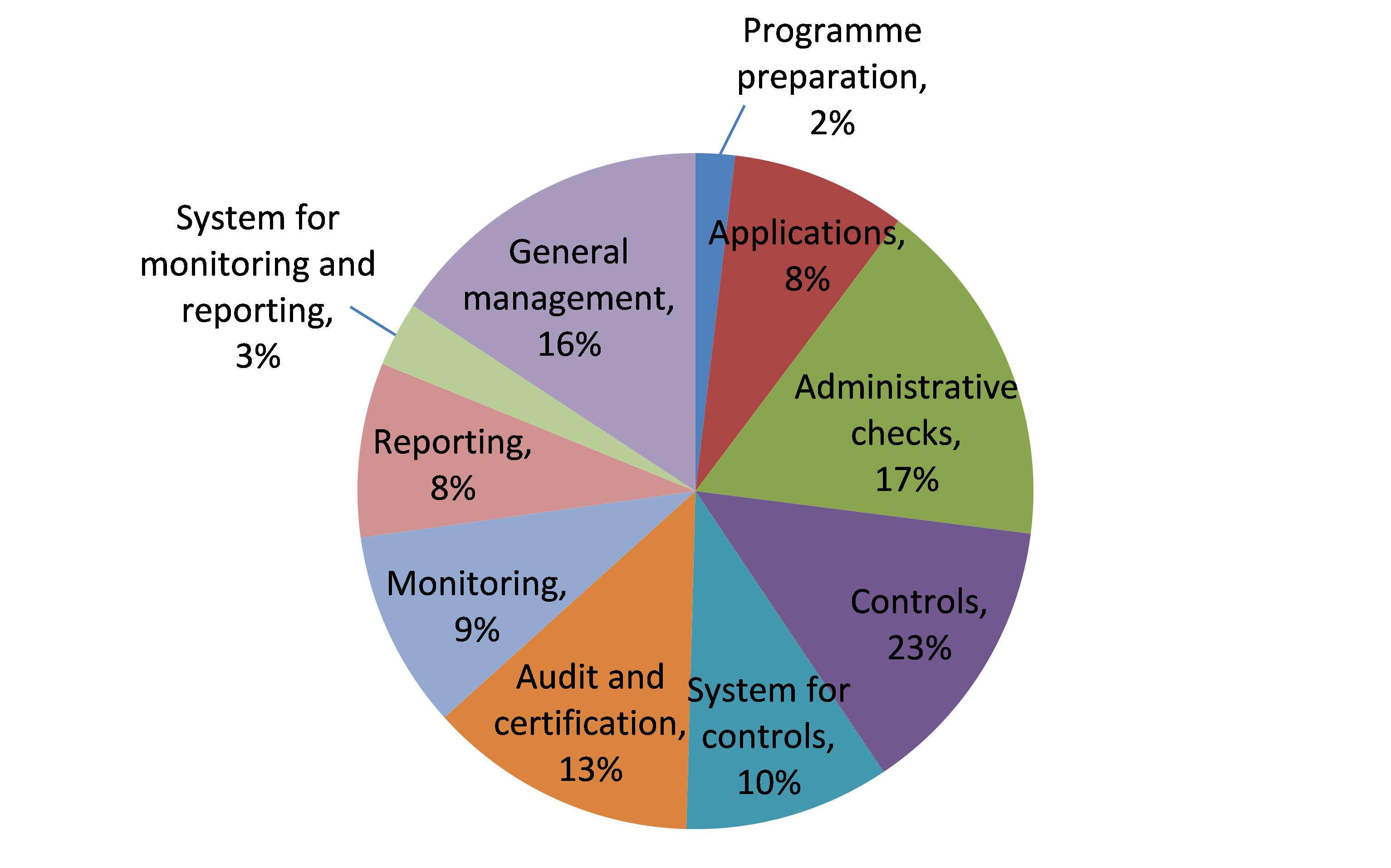

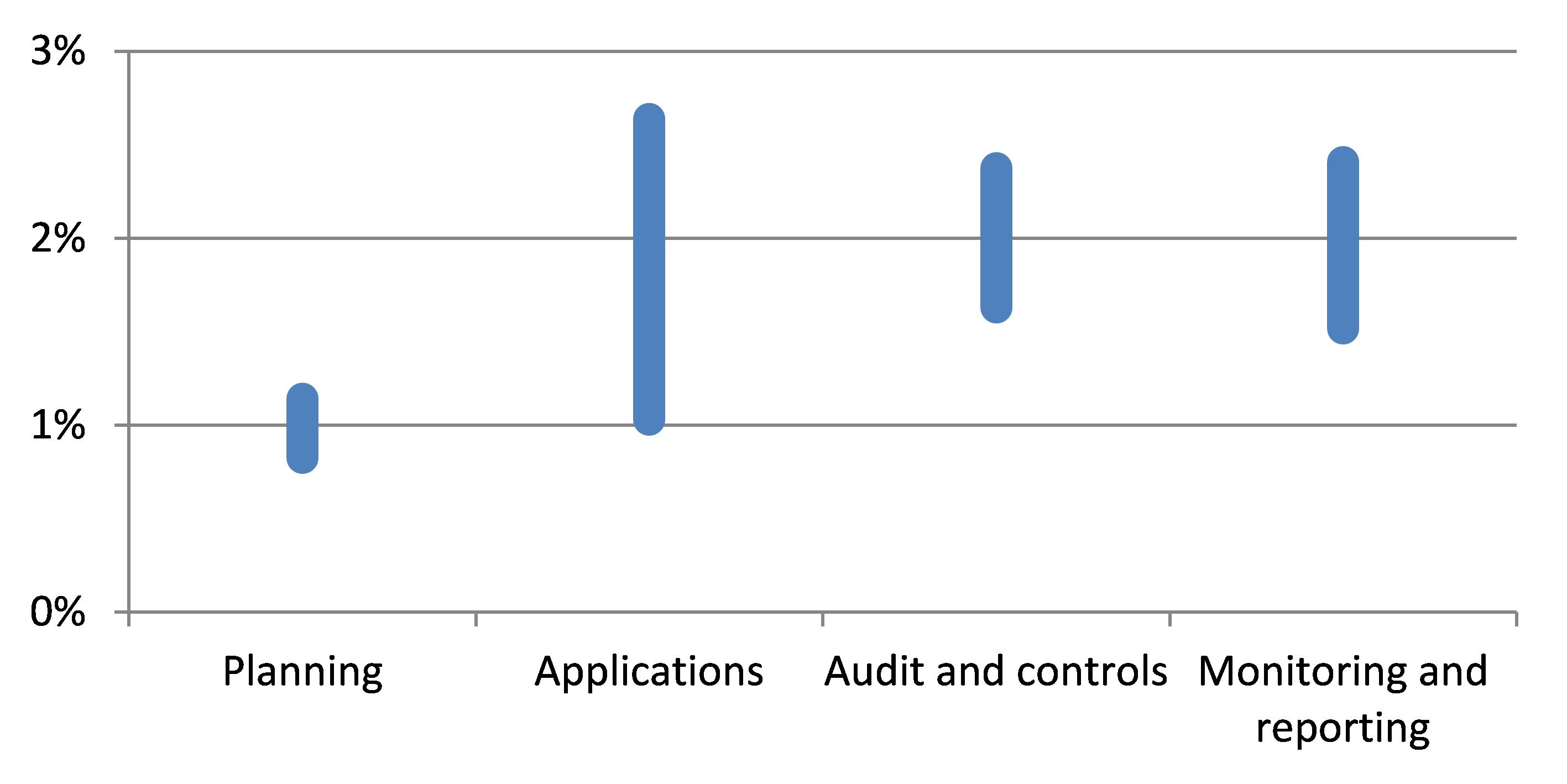

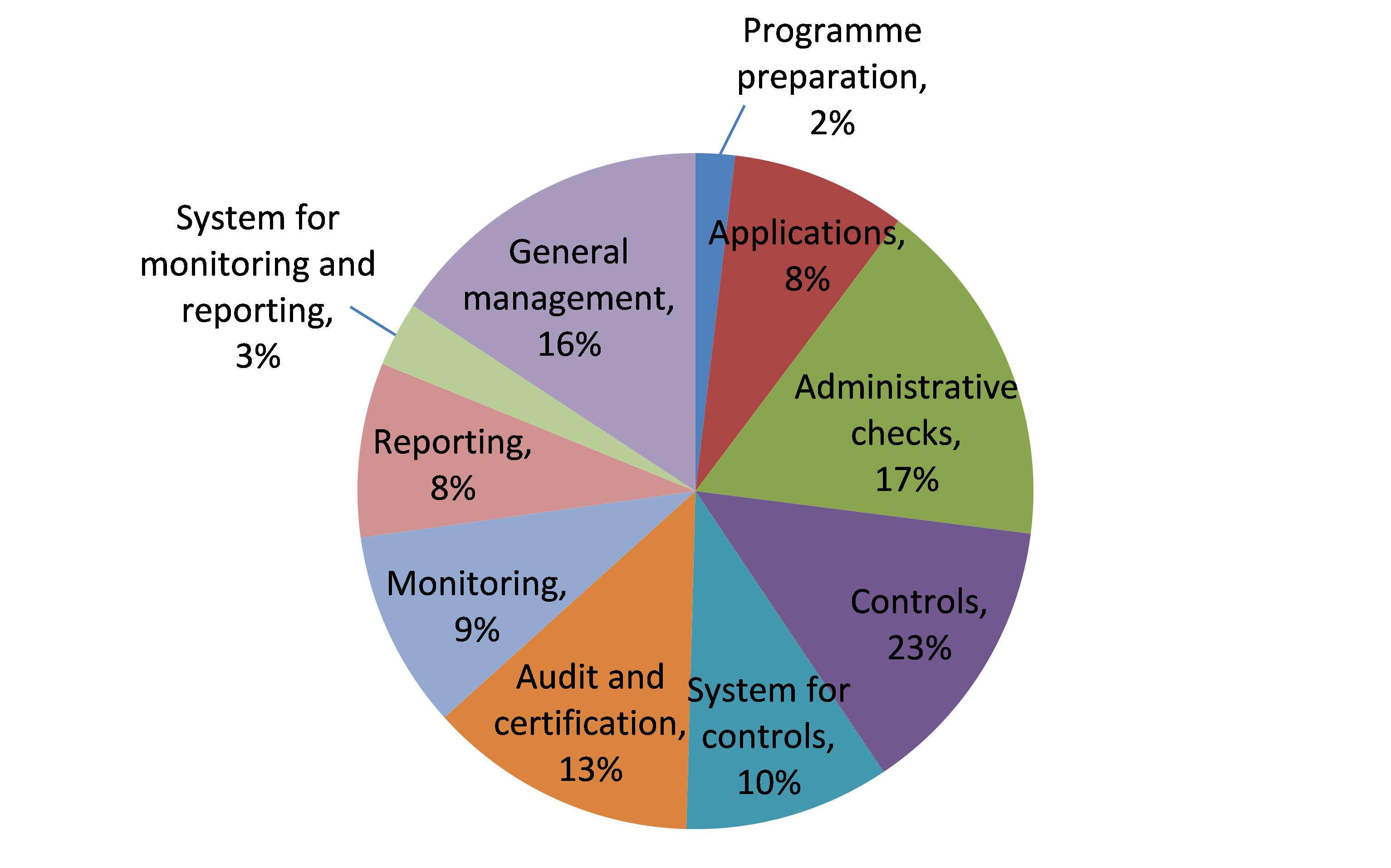

|